By Donald Burleson

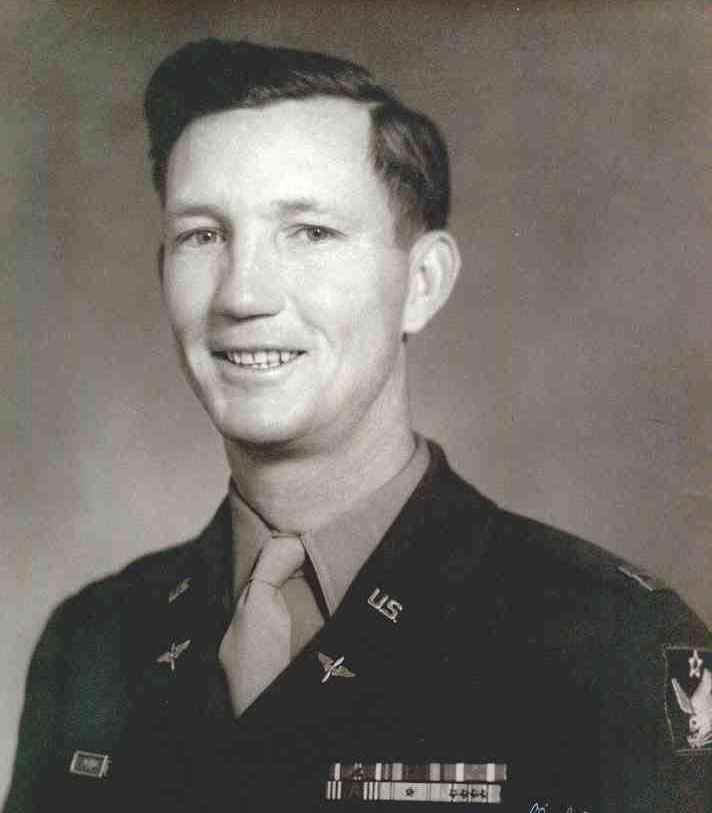

Louis Francis Burleson was born on November 30th 1914 in a farm house in New London North Carolina. Louis was the last child of Corinna and J. V. Burleson, being born when J. V. was 44 years-old. Louis was a very athletic young man and earned high school letters in football, basketball and baseball. After graduation Louis went to live in New York City after his graduation from high school.

In 1936 Louis joined the US Army Air Corp and went to Hickam field in Hawaii, where he learned aircraft mechanics and served as pitcher for the Army team in Hawaii.

Gifted with a photographic memory and a natural ability in mathematics, Louis supervised poker games in the wealthy casinos on Waikiki beach. By taking 10% of each pot to keep the game honest, Louis earned over $1,000 per month, far more than his meager military pay of $36/month. By 1938, Louis was promoted to sergeant, earned a solo pilots license and had a nice off-base apartment, where he hired a Navy Captain’s wife to do his cleaning.

In 1939 Louis F. Burleson was transferred to Kirtland Field in Albuquerque, New Mexico. It was there in 1941 that he met Virginia Griffiths, who he married in September, less than 90 days before Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of WWII. His new wife, Virginia (Ginger) Griffiths was a native of Ireland, and was born on Feb 15th, 1920 in Dublin. She immigrated to the United States with her mother Geraldine to New York City in 1921. Less than a week after their wedding, Louis was promoted to Technical

In 1939 Louis F. Burleson was transferred to Kirtland Field in Albuquerque, New Mexico. It was there in 1941 that he met Virginia Griffiths, who he married in September, less than 90 days before Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of WWII. His new wife, Virginia (Ginger) Griffiths was a native of Ireland, and was born on Feb 15th, 1920 in Dublin. She immigrated to the United States with her mother Geraldine to New York City in 1921. Less than a week after their wedding, Louis was promoted to Technical ![]() Sergeant and transferred to Clark Field in the Philippines where he was assigned to the 19th bomb group of the 5th Air Force as chief mechanic for the fleet on several dozen B-17 bombers. It was at Clark Field where Lou first encountered combat when he fought the Japanese on December 7th, 1941. Listening to radio reports of the destruction of Pearl Harbor, the radio announcer said that Clark Field had also been bombed. Taking the hint, the B-17s were moved to a safer area, but less then 10 minutes after the announcement a wave of more than 50 Japanese bombers devastated Clark Field, destroying more than half the U.S. air power in the Pacific theater.

Sergeant and transferred to Clark Field in the Philippines where he was assigned to the 19th bomb group of the 5th Air Force as chief mechanic for the fleet on several dozen B-17 bombers. It was at Clark Field where Lou first encountered combat when he fought the Japanese on December 7th, 1941. Listening to radio reports of the destruction of Pearl Harbor, the radio announcer said that Clark Field had also been bombed. Taking the hint, the B-17s were moved to a safer area, but less then 10 minutes after the announcement a wave of more than 50 Japanese bombers devastated Clark Field, destroying more than half the U.S. air power in the Pacific theater.

As the Japanese invaded the Philippines, Louis fled to Luzon where the last holdouts prepared a stand against the Japanese invaders. After General Macarthur was order to leave Luzon, morale declined as the Americans were short on food and supplies and vastly outnumbered by the Japanese.

As the Japanese invaded the Philippines, Louis fled to Luzon where the last holdouts prepared a stand against the Japanese invaders. After General Macarthur was order to leave Luzon, morale declined as the Americans were short on food and supplies and vastly outnumbered by the Japanese.

Clark Field, December 1941 Louis was ordered to take the last ship from Luzon, leaving his compatriots to face certain defeat. Those left behind were captured and were forced to march north though the jungle in the infamous “Bataan Death March”.Louis Burleson fled with the 5th Air Force to New Guinea, and later to Australia in early 1942.

The 19th bomb group suffered heavy losses from the daring daylight raids and they sought to undertake a new bombing method that would minimize casualties. During his time in Australia, Louis flew fifty-two combat missions as a gunner and flight engineer in the remaining B17 bombers. He received the Distinguished

The 19th bomb group suffered heavy losses from the daring daylight raids and they sought to undertake a new bombing method that would minimize casualties. During his time in Australia, Louis flew fifty-two combat missions as a gunner and flight engineer in the remaining B17 bombers. He received the Distinguished

![]() Flying Cross on two occasions, each time for meritorious valor in combat, and also received the Air Medal. Louis F. Burleson’s first Distinguished Flying Cross commendation reads:

Flying Cross on two occasions, each time for meritorious valor in combat, and also received the Air Medal. Louis F. Burleson’s first Distinguished Flying Cross commendation reads:

LOUIS F. BURLESON, 6882468, Technical Sergeant, Headquarters Squadron, 19th Bombardment Group (H), Air Corps, United States Army. For extraordinary achievement while participating in the aerial flights in the Southwest Pacific Area from December 8, 1941 to

November 9, 1942. During this period, Sergeant Burleson participated in more than fifty operational flight missions during which hostile contact was probable and expected. These flights included long-range bombing missions against enemy airdromes and installations and attacks on enemy naval vessels and shipping.

Throughout those operations, Sergeant Burleson demonstrated outstanding ability and devotion to duty. As a gunner on the B17’s, Lou’s expert marksmanship with the 50 caliber machine guns sent many Japanese fighter planes crashing into the Pacific Ocean. Louis Burleson once stated that he believed that he shot down at least ten enemy aircraft using a technique that he discovered from the nighttime bombing raids. Unlike the B-17 which has a protecting inner lining to seal-up bullet holes, the Japanese fighters did not have this feature. By loading his machine gun with incendiary rounds he was able to explode the fighters with a well-placed shot into the wings.

Actual Photo of the B-17 mission over Rabaul

Actual Photo of the B-17 mission over Rabaul

Louis Burleson was cited for extraordinary heroism and commissioned as a Second Lieutenant after he invented flare racks for the B-17 that allowed the 5th Air Force to do night bombing mission, saving the lives of many crew members.

Major Bernard Schriever, a newly-minted Major fresh from Graduate school at Stanford University, joined the 19th bomb group in Australia and directed Burleson’s effort to perfect the flare racks. In less than 90-days Schriever recommended Louis Burleson for an officer’s commission. Schriever was the pilot of Louis Burleson’s crew on a famous bombing raid there Schriever used the B-17 as a dive bomber, destroying Japanese battleship in an act of extreme heroism. This recollection is from an article about General Schriever in “Air Force” magazine:

“They flew in a formation of about a dozen B-17s in a night raid on Rabaul. Their airplane carried the flares and half the regular bomb load. The flare system worked well, but Schriever wanted to check on the bombing results, so they made another circuit over the target area. Flak was heavy but ineffective at the 10,000-foot altitude from which they were bombing.

As they turned, the No. 3 engine burst into a ball of flames. Dougherty, in the left seat, feathered the prop and shut the engine down. They still had bombs on board but did not want to set up another bombing approach. A quick conference on the intercom led to a decision: They would dive-bomb the ships in the harbor.”

General Schriever later became the father of missiles and space in the Air Force. General Schriever’s recommendation for Louis Burleson reads:

Technical Sergeant LOUIS F. BURLESON, 6882468, has been directly under my command for over three months. During this time has performance of duty has been superior. He has shown a keen interest in all projects which, in any way, might improve our effectiveness against the enemy.

He not only installed the first flare rack in B-17 aircraft but also went on the first two combat missions on which flares were used. His habits and character are excellent and his attention and devotion to duty unquestioned. It is my opinion that he is well qualified to perform the duties of commissioned grade.

Louis Burleson was transferred to Pyote Texas in November of 1942 to serve as an instructor of aircraft mechanics. Being a very creative fellow, Louis invented several tools for aircraft warfare, and was transferred to the Pentagon in Washington, DC where the Army Air Corp patented several of his inventions. A document was located in which Louis Burleson was recommended to receive the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest medal awarded in the United States. The DSC, usually given only to generals, was offered to Lou for his outstanding contribution to air warfare in the South Pacific Theatre. In typical fashion, Lou declined, stating that he was not worthy of such a great honor. Louis F. Burleson was then assigned to Muroc AFB in California where he was in charge of aircraft maintenance. It was there that he became friends with Chuck Yeager, who later went on to be the first person to break the sound barrier. Louis Burleson also volunteered for service in Korea and was the project officer for the 6127th Air Terminal group where he was promoted to Major and won the Bronze Star for his Valor during an attack. His brother Vincent Burleson also served in Korea and received the Air Medal for distinguished aerial achievement in B-29 bombing missions.

Louis F. Burleson was injured numerous times in WWII and Korea, most notably a back injury and a loss of hearing from being near an explosion. His selfless devotion to duty was apparent when he refused to seek treatment for these injuries for fear of loosing combat status, even though he could have been awarded the Purple Heart and transferred to a non-combat role. Louis Burleson was forced to accept a medical retirement in 1958 at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. As a disabled veteran, he spent the rest of his life championing the rights of those who were injured in service to their country.

Personal Notes:

Louis was originally named “Kenneth”, but his mother changed his name to the Catholic name “Louis” in 1918 after converting to Catholicism. Virginia attended the University of New Mexico and earned a degree in general studies in 1942. Ironically, Lou and Ginger both lived in New York City in the 1920’s and lived a few blocks from each other for several years. They both remembered the construction of the Empire State Building, but it would be many years before they would meet in Albuquerque. They met while Ginger was playing with her pet rabbits on her front lawn and Lou drove by in a jeep. Lou stopped to introduce himself, and they immediately found themselves attracted to each other. They were married in September of 1941. Lou once remarked that the best advice he ever received from his father was the saying “There’s always room at the top”. He interpreted his father’s advice to mean that a person could always rise to the top, and the only impediment to achievement was a lack of confidence in your own abilities. Lou was an expert marksman, and was rated as an expert rifleman by the U.S Army Air Corps. (see appendix) This is not surprising, because the number one priority with the Burleson’s was to teach their children proficiency with a rifle. Superior marksmanship was a very important skill, and was held in high regard by all past generations of the Burleson family.

Lou enjoyed hunting, and at one time owned more than 15 rifles. Lou passed the Burleson tradition of marksmanship on to his son, Don. Lou and Ginger had one child, Donald Keith Burleson, while they were stationed in Aurora Colorado. Following Lou’s retirement in 1958 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, the couple moved back to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Lou continued the Burleson tradition of serving Oyster Stew on Christmas Eve, much to the disgust of his family. Other family traditions were Christmas stockings filled with fresh oranges and nuts. Lou also enjoyed playing Cribbage and Blackjack with his son. Lou developed a severe hearing loss and crippling arthritis after his retirement from the Air Force, but he always maintained a cheerful disposition and occupied his time by doing volunteer work for the Republican party. An avid reader, Lou spent his last days keeping up with current political and national events. As Lou’s health continued to deteriorate, he was eventually confined to a wheelchair, and died on September 26, 1975 at the age of 60. Lou was buried in the Santa Fe National Cemetery with full military honors, including a twenty-one gun salute. His wife Ginger died six months later from lung cancer, and is buried next to him. Don’s line is Louis F. Burleson, J.Vespasian (Pace) Burleson, John Wesley Burleson, Joseph, Isaac Sr.